.

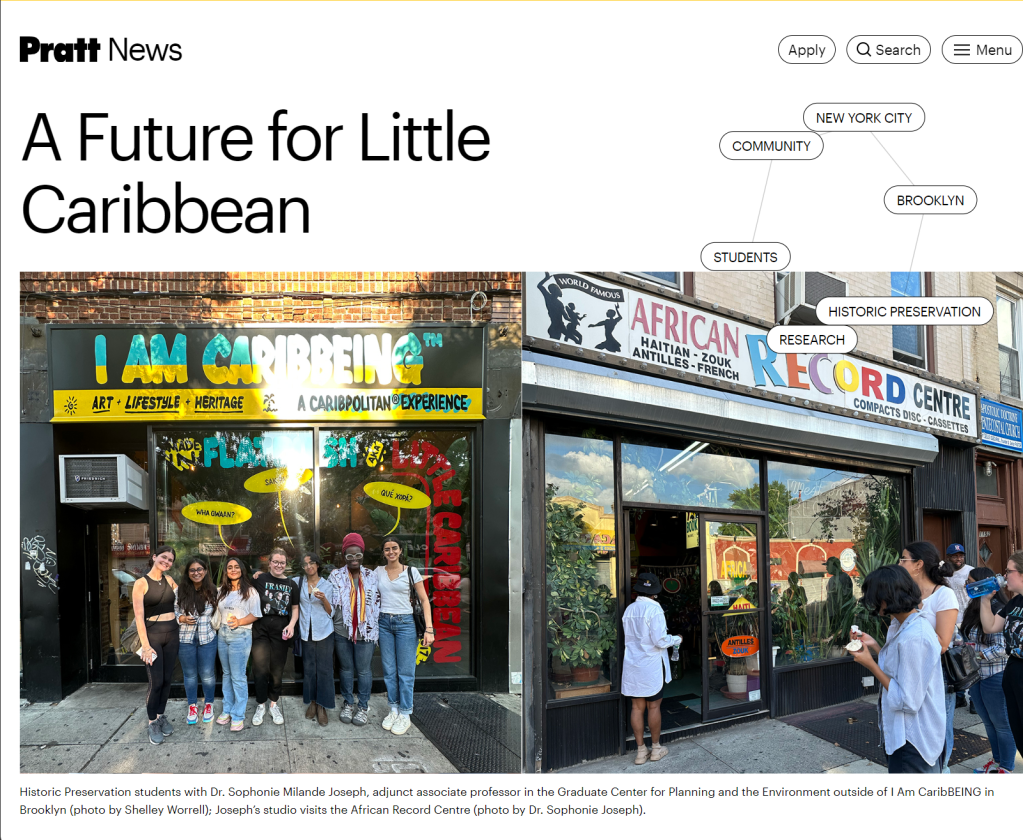

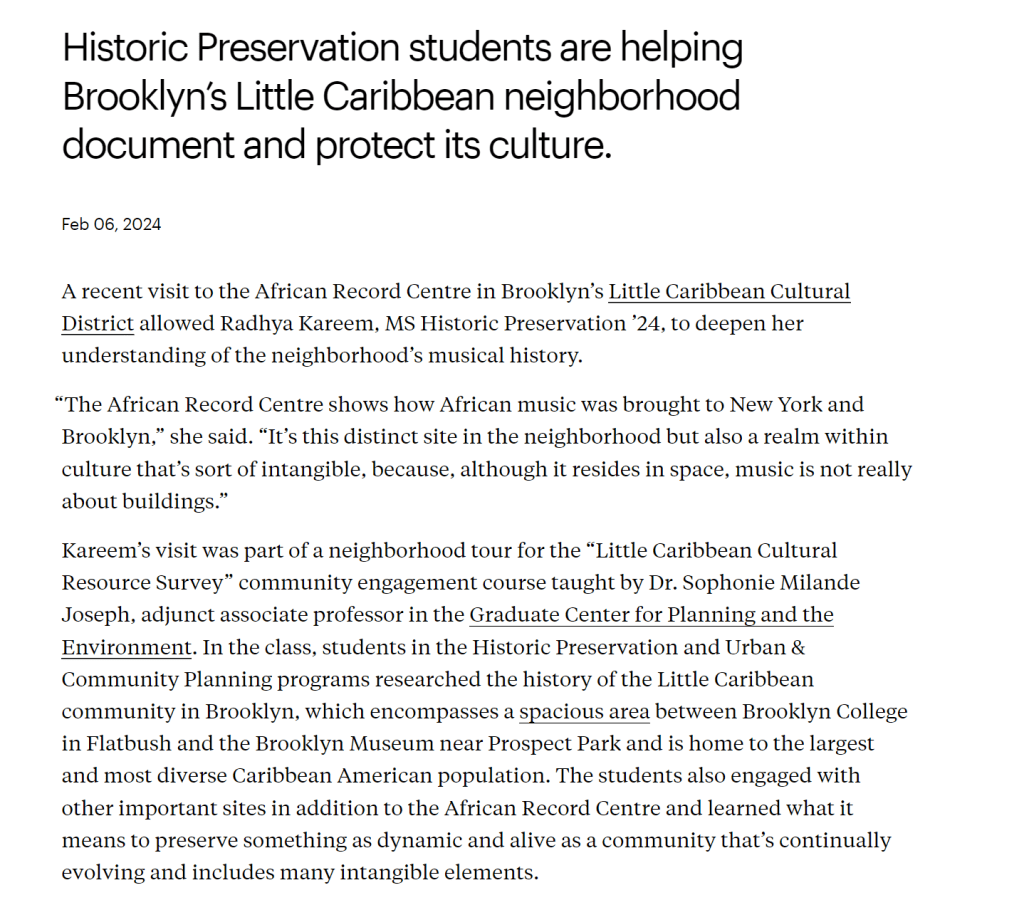

Read more at: https://www.pratt.edu/news/a-future-for-little-caribbean/

.

Caribbean Diasporic Heritage Month

.

.

Illustrations for Social Media Campaign for Caribbean Diasporic Heritage Month for Dr Sophonie M. Joseph. Deenps Bazil, Esmerelda Simmons, Lorraine Mangonès, Michele Oriol, Michelle Duvivier, Régine Romain, Rose May Guinard, Sabine Malbranche, Shanna Sabio, Sonide Simon, Sophonie Joseph, Tatiana Wah, Yvena Despagne.

.

Sonic Genealogies

Musical Styles: Carnival Routes and Sonic Genealogies

A major signifier of Brooklyn becoming the new epicenter of the Caribbean community was the migration of the West Indian Day Parade Carnival[1] and its music from its origins in Harlem by way of the Caribbean. Between 1965 and 1980, 300,000 immigrants from Jamaica, Trinidad, Haiti, Barbados, Grenada, Coastal Guyana, and other small Caribbean Islands; made their way towards New York[1]. [2] A large density of these groups settled in central Brooklyn neighborhoods, including Bedford Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, East Flatbush, and Prospect Heights. These immigrants had the ability to move back and forth, thereby acting as a bridge to cross-pollinate musical influences from back home to Carnival celebrations across the city.[2]

Steel Pan and Street Navigation

In 1966, Winston Munroe[3] , a skilled steel pan player from Trinidad, arrived at JFK and found his way to the [4] informal Crown Heights street processions and block parties taking place. The festivities include a group of musicians playing tenor pans, irons, and conga drums, moving around St. Johns, Classon, and Washington Avenues.[5] Munroe witnessed what would come to be the beginnings of the first West Indian parades[6] to take place in Brooklyn. The earliest informal parades in Brooklyn were shepherded by Trinidadian Lionel “Rufus” Gorin in 1960. Gorin held unofficial outdoor carnivals near his home at 105 Lefferts Place in Brooklyn.[7] These celebrations expanded over time and became the full-blown Carnival celebrations we know today. Witnessing the Carnival in Brooklyn today is to see the synthesis of different musical styles from the Caribbean coalesce into a cacophonous whole. But Steel Pan is one of the primary genres to dominate the music scene in NYC’s diasporic Caribbean community. The Steel-Pan refers to the use of either steel drums or pans to create music.[3] It is an integral part of Caribbean Carnival music[8] [9] . Additionally, J’Ouvert or ‘The Break of Day’ processions which were incorporated into Trinidad’s ‘Pre-Lenten’ Carnival was characterized historically by the use of steel pan music.[4] It consisted of African percussion, witty satirical singing, sardonic costuming and lively steelband music. It evolved from the 19th century Canboulay festivals which were held by ex-slaves who gathered to masquerade, sing and dance in the spirit of emancipation.[5] The Brooklyn Labor Day Carnival was characterized by the Trinidadian model of large masquerade bands dancing to popular calypso music. Some of the music on the Eastern Parkway celebrations included live steel bands that either showed up themselves or were hired by individual masquerade bands to accompany them.[6]

In 1972, Brooklyn’s first annual ‘Pan-orama’ contest was established as part of the Labor Day Carnival festivities in Brooklyn as part of the Brooklyn Museum’s concert lineup. The contest marked the expansion of the event into the borough’s premier cultural celebration.[7] The Steel band competition is not to be taken lightly and has a repertoire of famous musicians and judges. The judging panel has included gems from the past, including Daphne Weekes, the first female calypso bandleader in the U.S. Originally a pianist from Trinidad, she moved to the U.S. in 1939. She led the “Daphne Weekes and her Versatile Caribbean Orchestra,” a 12-piece band and gained immense popularity worldwide, performing in major cities. In her later years, Weekes continued playing for senior citizen centers in Brooklyn[10] [11] and was a featured performer at the Annual Senior Citizen Day at Lincoln Center.[8]

Sonic Synergies and Exchanges

By the mid-1960’s Brooklyn became the epicenter of Caribbean musical and Carnival activities.[9] Set within the backdrop of different world powershifts, music in the Caribbean was going through innovation and transformation in response to authoritarian regimes. Technological innovations back in the Islands were being transposed to New York, creating new soundscapes like Hip-Hop. Questioning common perceptions of New York being the birthplace of Hip Hop; innovations in ‘record-engineering’ had already began in 1960s Jamaica. Jamaican born DJ Kool Herc (Clive Campbell) brought some of these new innovations with him when he moved to New York in 1967. He imported a ‘sound system experience’ to the New York audience. It was during the 60’s that many innovations in DJ technology took place. This included using two turntables to play two copies of the same record over and over across two turntables. DJ Kool’s manual edits using two record copies coined the term ‘Break Beat.’[10]

Many musical synergies were made possible by the widespread dissemination of Caribbean music and other genres by the increasing numbers of Brooklyn-based, Caribbean diaspora-owned record labels and record stores. Between 1960 and 1965 these companies played a crucial role in the production and distribution of Soca music[11]originating in Trinidad and Tobago, the genre has been used as a form of resistance and identification for Trinbagonians and other West Indians in the diaspora.[12] Some key record labels in Brooklyn that began distributing, recording and mixing the newly popular Soca genre included Straker’s Records Label, Charlie’s Records Label and B’s Records. Granville Straker, a St Vincent native who moved to Trinidad, came to Brooklyn in 1959. Initially, he started a car service store at 242 Utica Ave but then it became a record store and label as well. Eventually, he had three record stores in the heart of Brooklyn. He became a one-man operation taking over scouting talent, record mixing and engineering, a record distributor, and a concert promoter.[13] Charlie’s Record Label was owned by Rawlson Charles, a native Tobagonian who arrived in New York in 1967 with only a suitcase and a Lord Kitchener album[12] . His store and label was located at 1265 Fulton Street. The label distributed one of the earliest Soca recordings: Lord Shorty’s ‘Sweet Music’ in 1976, Calypso Rose’s ‘Sweet Tempo,’ and many others. B’s Records started off in 1981 by Michael Gould, Trinidad-American entrepreneur. Invested in a state of the art studio at 1285 Fulton Street and between 1982-1988, produced 120 albums. These consisted of various calypso/soca stars including Lord Kitchner, the Mighty Sparrow, Black Stalin, Lord Nelson, Penguin and Explainer.[14]

Specific to Flatbush, The African Record Store, nestled in the core of Prospect Lefferts Garden has been the nexus of sonic cultural exchange but has also been the bridge to the distribution and promotion of African music. The Francis Brothers first opened the store in 1969 and connected major Nigerian musicians to the soundscapes of Brooklyn and greater New York. Roland spent a year in Nigeria[13] [14] [15] meeting artists Rex Lawson, Fela Kuti, Ebenezer Obey, Dele Ojo and imported their music to the rest of the world.[15]

During the same time, a shift was observed in the prevalent Carnival music during the Brooklyn Day Parade. Soca music, the fast-paced derivative of calypso that emerged in the 1970s, replaces its predecessor as the most popular carnival music genre.[16] It was created by the calypsonian, Garfield Blackman, better known as Lord Shorty or the “Father of Soca,” who “began experimenting with East Indian rhythms, using instruments such as the dholak, tabla and dhantal and fusing them with the calypso beat”. It is closely linked to the Trinidadian Carnival and is known for its party anthems and emphasis on unity.[17]

By the mid-1970s Soca music began to dominate the Brooklyn Eastern Parkway Labor Day celebrations. Soca is a Trinidadian pop style that merges Calypso and Black American Soul and Disco Music. The sound was manufactured by record spinning Deejays. The traditional Steel Band primary position was surpassed by Soca due to the ease of playing and creating Soca music by sound systems that could be easily mounted on trucks.

The Indian influence in soca faded out early on but resurfaced in the last decade with the emergence of new forms like chutney-soca[18] defined in 1987, with the debut of Drupatee Ramgoonai’s first album Chutney Soca.[19] These hybrid blends represent the complex geographic synergies that come to define Caribbean immigrant groups like the Indo-Guyanese. Rupa Pillai in ‘A Question of Voice: Indo-Caribbean American Feminism through Music in New York City,’ interviews long-time residents of Indo-Caribbean descent in Brooklyn. In her conversations, she traces hybrid street soundscapes that emerged. One of her interviewees remarks:

‘I heard the congo drums, salsa, merengue every time I opened the window or went down the street to buy milk. There was a festivity, joy in the Latin people. And I was surrounded by so many different types of music’.[20]

By 1990, WIADCA (West Indian American Day Carnival Association) officially introduced the Panorama contest in Brooklyn that offered a cash prize for Steelpan Bands. This led to a revitalization of the genre and tradition.[21] In 1994, Earl King set up J’Ouvert City International (JCI), a not for profit organization. It was formed as an attempt to bring order and structure to the parades. JCI created a bridge between city authorities to retrieve permission to parade from Woodruff Street and Flatbush Avenue across what is now called ‘Empire Boulevard,’ down Nostrand Avenue to Linden Boulevard at 3 o’clock on Labor Day morning. According to the annual program book for J’Ouvert celebrations, there is an emphasis on performing ‘Steelpan music only.’ This emphasis on traditional music vis-a-vis the manufactured mounted sound system music is what differentiates Flatbush celebrations from the Eastern Parkway ones.[22] Concurrently, Earl King and other associates initiated different competitions surrounding the J’Ouvert parade. These consisted of creating viewing sites for competing Steel-Bands and Masquerade bands that were set up along the parade routes in front of sponsoring businesses. Some sponsoring businesses include Allan’s Caribbean Bakery(founded 1961; located at 1107, 1109, and 1111 Nostrand Avenue), Scoops[16] [17] (founded 1984, located at 624 Flatbush Avenue), Mike’s International Restaurant.[23] This is why different Mas-Camps are set up at certain addresses and are in proximity to various Caribbean owned businesses, highlighting the relationship between present day Caribbean owned businesses celebrating intangible sonic and cultural traditions. Trophies were given out for categories of ‘best steel band calypso tune,’ ‘bomb-tune,’ ‘mas costume.’[24] By 1997, more cash awards and categories were introduced including an award for 1st, 2nd and 3rd place for Best Calypso tune, Bomb tune, Mas Band costume and individual Male and Female costumes.[25] A marked difference between the celebrations on Eastern Parkway and those primarily for J’Ouvert within the Flatbush area is an emphasis on ‘Steelpan music only’ and prioritizing traditional music v. the manufactured mounted sound system music.[26]

Broadcasting Bridges: Radio Stations as Oral Culture

Another important aspect in the modes of Sonic Genealogies is the emergence of Haitian Radio and other Latin American diasporic stations in Brooklyn. According to Mann,

‘For immigrants in particular, radio sounds mark identity and community and (re)claim social spaces of work, commutes, and the home’.[27]

There was an essential role that Haitian Radio played in particular in community-building, activism, and citizenship for Haitians who arrived in the U.S in the 1980s.[28] Diasporic listeners found it to be the only way to keep up to date with news from back home, listen to conversations in Creole and enjoy Konpa music played during intervals.[29] A string of these stations are lined along Nostrand Avenue including Radio Soleil (1622 Nostrand Ave), Radyo Panou (1685 Nostrand Ave) and Radio Triomphe (1716 Nostrand Ave).

Radio Soleil was founded in 1992. Ricot Dupoy has been a DJ and broadcaster at the station since the radio’s inception and outlines the importance of how Radio Soleil acts as an incubator for human rights activism, housing assistance, family reunification, and preservation of culture.[30] In 1998 it was observed to be staffed by 20 journalists, all first generation Haitian immigrants. Some of these had attended journalism school back in Haiti and most of them had worked at radio stations back at home. On arriving in the US they found themselves at the margins of the American media market.[31]

Walking further along Nostrand Avenue, one reaches Radyo Panou, founded in 2010. It broadcasts news from Haiti, conversations in Creole and Konpa music. The station played an important role in disseminating news to the haitian diaspora in Brooklyn during a time of crisis. According to Dr. Jean-Claude Gilles, director of programming at Radyo Panou, many people contacted the radio station to find whereabouts of family and relatives in Haiti in the aftermath of the earthquake and messages were relayed over back to Haiti through sister radio stations.[32] Radio Panou hence acted as a telegraph service of sorts. Jeffrey Joseph, the vice president and general manager of the station, narrates that the station had received hundreds of calls from New York families looking to locate relatives on the island.

The earliest record of Radio Triomphe’s (1716 Nostrand Ave) existence is 2014. It’s broadcasts focus on news from Haiti, and play a wide array of latin american music genres including kompa, salsa, jazz and more. Although rooted in broadcasting from a location, Triomphe like all other radio stations acts as a community hall of sorts for the Haitian diaspora. It provides functions including broadcasting news, local events and topics of interest that would otherwise not be covered in western news outlets like the state of educational, agricultural, health and political affairs in Haiti. Essentially it aims to keep Haitian cultural heritage alive through aural means.[33]

Kings Theatre and the Caribbean Music Awards

Fast forward to 2023, the Caribbean Music Awards held on 31st August marks a monumental occasion in the recognition of Caribbean music as a distinct, vibrant, and diverse musical landscape. A popular Caribbean American podcast, identified the event to award contributions to a wide array of music genres, including Reggae, dancehall, Kompa, Soca, and Zouk.[34] Renowned artist Wyclef Jean, hosted the awards this year. He has had a historical connection to Brooklyn, as depicted in his 1997 song “Touch Your Button Carnival Jam,” which vividly captures the essence of the annual West Indian Labor Day Parade on Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway.[35]

Brooklyn serves as the chosen location for its cultural richness and representation of being a melting pot of Caribbean cultures. The timing of the awards coincides with a year of celebrations culminating in various Carnivals geographically. This includes celebrations in Miami and in the wider geosphere of Caribbean countries. Brooklyn, hallmarked by a diverse Caribbean-origin demographic, spanning various age groups makes the Brooklyn’s Kings Theatre (1027 Flatbush Ave) a strategic choice. Situated in the heart of Little Caribbean, the site adds to the cultural resonance of the awards ceremony.

[1] Segal, Aaron. “The Political Economy of Contemporary Migration.” Globalization and neoliberalism: The Caribbean context (1998): 225

[2] Allen, Ray. ‘Carnival Comes to Brooklyn’, Jump Up!: Caribbean Carnival Music in New York City. Oxford University Press, 2019. p.85

[3] Guilbault, Jocelyne. “Jump Up!: Caribbean Carnival Music in New York, by Ray Allen.” New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 95, no. 3–4 (October 14, 2021): 391–92. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134360-09503024.

[4] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.256

[5] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.256

[6] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.260

[7] Allen, Ray. ‘Carnival Comes to Brooklyn’, Jump Up!: Caribbean Carnival Music in New York City. Oxford University Press, 2019. p.89

[8] Weekes, Daphne. Daphne Weekes Collection, n.d.

[9] Guilbault, Jocelyne. “Jump Up!: Caribbean Carnival Music in New York, by Ray Allen.” New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 95, no. 3–4 (October 14, 2021): 391–92. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134360-09503024.

[10] Lohlker, Von Rüdiger. “Hip Hop and Islam: An Exploration into Music, Technology, Religion, and Marginality,” 2023.

[11] Allen, R., 2020. Harlem calypso and Brooklyn soca: Caribbean carnival music in the diaspora. In Music, Immigration and the City (pp. 9-26). Routledge. p.8

[12] Guilbault, Jocelyne. “Jump Up!: Caribbean Carnival Music in New York, by Ray Allen.” New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 95, no. 3–4 (October 14, 2021): 391–92. https://doi.org/10.1163/22134360-09503024.

[13] Allen, R., 2020. Harlem calypso and Brooklyn soca: Caribbean carnival music in the diaspora. In Music, Immigration and the City (pp. 9-26). Routledge. p.38

[14] Allen, R., 2020. Harlem calypso and Brooklyn soca: Caribbean carnival music in the diaspora. In Music, Immigration and the City (pp. 9-26). Routledge. p.41

[15] Afropop Worldwide. “Afropop Worldwide | The Francis Brothers: African Record Center.” Accessed October 28, 2023. https://afropop.org/articles/35172.

[16] “Gantt, Deidre R. “”Talking Drums: Soca and Go-Go Music as

Grassroots Identity Movement”” Rhythms of the Afro-Atlantic World, Nwankwo, Ifeoma, ed.. University of Michigan Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.89.”

[17] National Library, ‘Calypso Study Guide’

[18] National Library, ‘Calypso Study Guide’

[19] “Chutney Soca Succession | Caribbean Beat Magazine.” Accessed December 9, 2023. https://www.caribbean-beat.com/issue-123/chutney-soca-succession#axzz8LPaRBZwo.

[20] Pillai, Rupa. “A Question of Voice: Indo-Caribbean American Feminism through Music in New York City.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 47, no. 1–2 (2019): 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2019.0024.

[21] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.262

[22] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.262

[23] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.263

[24] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.263

[25] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.263

[26] Allen, Ray. “J’ouvert in Brooklyn Carnival: Revitalizing Steel Pan and Ole Mas Traditions.” Western Folklore 58, no. 3/4 (1999): 255–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/1500461. p.262

[27] Mann, Larisa Kingston. “Booming at the Margins: Ethnic Radio, Intimacy, and Nonlinear Innovation in Media,” 2019.

[28] Exumé, David. “Haitians Live for News.” In Embodying Peripheries, edited by Giuseppina Forte and Kuan Hwa, 1st ed., 282–95. Florence: Firenze University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.36253/978-88-5518-661-2.14.

[29] Ian Coss, ‘Haitian Radio On American Airwaves’ Afropop Worldwide, Podcast Audio, 2016. https://soundcloud.com/afropop-worldwide/haitian-radio-on-american-airwaves.

[30] Exumé, David. “Haitians Live for News.” In Embodying Peripheries, edited by Giuseppina Forte and Kuan Hwa, 1st ed., 282–95. Florence: Firenze University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.36253/978-88-5518-661-2.14.

[31] Exumé, David. “Haitians Live for News.” In Embodying Peripheries, edited by Giuseppina Forte and Kuan Hwa, 1st ed., 282–95. Florence: Firenze University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.36253/978-88-5518-661-2.14.

[32] Kaufman, Gil, MTV. “Haitians Rely On Old-School Communication In Earthquake Aftermath.” January 2010, Accessed January 24, 2024. https://www.mtv.com/news/c57hpo/haitians-rely-on-old-school-communication-in-earthquake-aftermath.

[33] “Radio Triomphe.” Accessed January 24, 2024. http://online-radio.eu/radio/30306-radio-triomphe.

[34] Rose, Mikelah. “Inside the Caribbean Music Awards in Brooklyn”. Style and Vibes Podcast. Spotify, September 2023, https://open.spotify.com/episode/5SxWfyUt1lLZBwrr9bvx3R Rose is a caribbean culture curator and community content creator belonging to Jamaican American roots

[35] Lamothe, Daphne. “Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race, and Identity in the Age of Globalization.” Biography 35, no. 2 (2012): 360–74. https://doi.org/10.1353/bio.2012.0020.